This is Part 2 on the topic of English dark-L. The main points from Part 1 are:

- It is totally possible to speak excellent English without learning about dark-L, and

- Incorrectly pronouncing dark-L can sometimes cause less clear speech.

- Plus, some easy advice for correcting dark-L and light-L pronunciation.

Part 2 provides additional clarification about:

- Why dark-L does not really need to be viewed as a separate sound for the purposes of language learners.

- How to explain dark-L to students in a simple, learner-friendly way, and avoid making it too complicated.

Because of some of the conflicting advice about dark-L, my purpose is to help English learners who have been confused about it, and to also provide helpful insights for English teachers.

But first, a fun little detour…

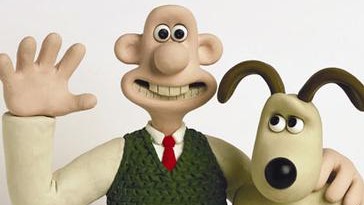

Have you seen the British show “Wallace and Gromit”? If so, have you noticed how the characters speak? The articulation for “L” has always caught my eye. The tongue tip is very visible between the teeth for “L”, just like for “TH”. The speech of these characters may be a bit exaggerated, but some native speakers sometimes do articulate “L” this way. These characters exemplify the importance of the tongue tip for English “L”, and it is also kind of fun to watch!

Back to Dark-L – Is it necessary to teach this?

For many learners of English, focusing on dark-L is generally not time well spent, especially if there are other more serious pronunciation problems that need improvement. However, if we do want to teach it, it may be better to not view it as a separate distinct sound or a completely different kind of “L”, because the difference between light-L and dark-L is actually pretty small.

On A Spectrogram

On a spectrogram, light-L and dark-L look pretty similar. The primary differences are that dark-L tends to have a longer time duration (in milliseconds), and that the 2nd formant (frequency band) tends to be a bit higher, somewhat similar to a high-back vowel, such as /u/. These are fairly minor differences and not exactly two different sounds.

The Native-Speaker Perspective

Native speakers are not aware of it! Native-speakers of English do not consciously make two different kinds of “L”, and young children are never taught to use different sounds. If you ask a typical native speaker – someone who is not a linguist, language teacher, or language learner – about the two different “L” sounds, they may just think that you are confused about English.

In contrast, it is not unusual for a native speaker of English to notice that there are different kinds of “T” sounds. For example, many are aware that the “T” in “butter” is often different for Americans compared to British speakers, or that the word “mitten” often has a different kind of “T”. However, the “L” sound is not something that English speakers typically talk about.

So, the difference is pretty small on a spectrogram, and it’s not enough to catch the attention of native speakers. And the reason it is not noticed by native speakers is because they regularly shift back-and-forth between light-L and dark-L very fluidly and very naturally.

Naturally, How?

For native speakers of English, shifting between the “dark” or “light” versions of “L” happens naturally based on the position of an “L” in a syllable.

Light-L: At the beginning of words/syllables. At the beginning of a word or syllable, the articulation of “L” is brief because it has the task of simply initiating the syllable. It has a short duration because the tongue tip needs to contact the top of the mouth just briefly and then immediately move on to the vowel that follows. Excess tension in the tongue body would be less conducive to this quick, brief movement. Therefore, the tongue has a medium amount of tension and the result is a basic light-L.

Dark-L: At the ends of words/syllables. The English language tends to have relatively strong endings for syllables. So, at the end of a syllable, “L” automatically has a slightly longer duration and a higher level of tongue tension, making it sound a bit stronger, which is suitable for the ending (or coda) of the syllable. The extra tongue tension is generated at the back of the tongue and it gives the “L” a heavier, fuller sound.

Shifting: Dark-L Reverts to Light-L

In spoken English, syllable boundaries shift in order to streamline articulation. Any syllable that starts with a vowel will typically borrow a preceding consonant when it has the opportunity. So, for example, a phrase such as “watch us”, when spoken in conversation, sounds more like “wa-chus”. Language teachers refer to this syllable-boundary-shifting as “linking”. This kind of linking is a very basic feature of spoken English, and it frequently causes a shift for “L”.

Because of linking, dark-L often reverts to light-L. For example, the word “call” has dark-L. But if a vowel follows it, such as in the phrasal verb “call off”, then the “L” is borrowed or “linked” in order to initiate the next part (“off”) and so it reverts to light-L. So, the verb “call off”, typically sounds like “ca-lloff”. Likewise, if a suffix which begins with a vowel is added, such as “-ing”, dark-L reverts to light-L so it can be the start of the second syllable, and it sounds like “ca-lling”.

Shifting: Light-L Converts to Dark-L

If a native-speaker makes a prolonged “L”, they end up with dark-L, because their tongue naturally tenses up when the sound is sustained. This can happen in speech, for example, when someone says “Oh, pllllllease!!!” emphatically (to express annoyance, disapproval or disagreement). Normally the word “please” has a light-L because the “L” is part of the beginning of the syllable, however, it becomes dark-L when it is held for a longer period of time.

Reframing Light-L vs. Dark-L: The Front End and the Back End of the Same Sound

Switching from light-L to dark-L is so natural and fluid, that it can be viewed as “2 sides of the same coin”. But I actually like to view it as two ends of the same sound. That is, a prolonged “L” sound initiates with a light-L tongue movement, but since it doesn’t move directly to another sound, the back of the tongue tenses to sustain it and makes dark-L. Thus, light-L is the beginning, or the front end of the sound, and dark-L is the back end. It is essentially one sound, not two different sounds, yet dark-L is sometimes oddly over-emphasized.

A Simplified Approach for Teaching

It is true that native speakers make dark-L in different ways and that it is not crucial for the tip of the tongue to make contact, etc. However, too many extra details are usually not helpful for the average non-native speaker of English, with a busy life, who wants to improve their English quickly. So, here is a de-complicated, more efficient way to explain light-L and dark-L which also helps avoid accidental mispronunciations that can sometimes happen.

1. Explaining the Location: “Where Does Dark-L Occur?”

Explanations for where dark-L and light-L occur are often fairly complicated and not easy to learn or remember. For example, the context is frequently explained something like this:

| Light-L happens: > At the beginning of a word, OR > The middle of a word before a vowel OR > In a beginning cluster such as ‘CL’ or ‘PL’. | Dark-L happens: > At the ends of words, OR > After a vowel, OR > Preceding a consonant at the end of a syllable such as ‘LD’ or ‘LP’. |

That is definitely NOT easy to learn or remember. However (good news!)… it can be described much more simply, like this:

| Light-L: Whenever “L” precedes a vowel sound. Dark-L: Anywhere else. (Whenever ‘L’ does not precede a vowel sound.) |

Here are some examples:

| light-L before a vowel sound | dark-L elsewhere |

| left | file (e=ø) |

| please | apple (e=ø) |

| belong | filter |

| willing | will |

| caller | holder |

A caution to English learners: Remember to watch out for silent “-E”. Light-L happens whenever “L” precedes a vowel sound, but not every vowel letter. For example, the word “silly” has light-L because the “L” precedes the vowel sound of the “Y”, but the word “uncle” has dark-L because “L” is the last sound in the word since the “-E” at the end has no sound.

Test Yourself!

Which words have dark-L? (The answers are at the bottom of the article.)

airflow / children / clear / example / explain / fall / follow / goal / light

longer / only / simple / spell / spell out / vowel / vowel sounds / while

2. The Back of the Tongue Quandary

The other main reason why dark-L can be confusing is because there are so many different explanations about the back of the tongue. Some teachers say the back of the tongue is raised, some say it is lowered, some say it moves forward, some say it moves back, and some say the throat tenses up, like for choking. (I even read a description that said the back of the tongue goes up to touch the soft palate at the back of the mouth… but, besides being almost physically impossible, that would cut off the airflow and not work at all!) So… which is right?

The truth is that it can be different for different native speakers, and at the same time, there is also a somewhat flexible range for the place of the tension. So for example, I previously explained (in Part 1) how to produce a very good quality dark-L by starting with an “O” sound, then unrounding the lips and raising the tip of the tongue to touch the top of the mouth, while maintaining the “O” position in the back. On the other hand, the tension in the back of the tongue can be produced farther back than the “O” position. This often happens in words that have /u/ followed by /l/, such as “cool”. For a native speaker, the tongue tension that initially starts at the position of the /u/ will then often move a bit further back for “L”.

That explains why different descriptions of dark-L seem to be contradictory (and why there is disagreement among linguists about whether it is velarized or pharyngealized or uvularized). The factor that they all have in common is the additional tension in the back part of the tongue muscle. So once again, we can simplify things for the learners with an explanation like this:

Dark-L is similar to light-L but the back of the tongue needs to be more tense

– the tension can occur wherever it feels most comfortable and natural.

That’s it! Some additional tension created anywhere in the back of the tongue will make a successful dark-L, and keeping the tongue tip at the light-L position will avoid the inadvertent “O” sound that some non-native speakers unintentionally make.

The Summary

Since English pronunciation and spelling patterns are very complex, it is always my goal to find less complicated ways to explain things and help make learning English more clear and efficient.

The key points for English “L” are:

- light-L and dark-L are really just 2 slightly different versions of the same sound

- the average native-speaker of English is not aware of them

- they naturally and regularly alternate based on the position within a syllable

- light-L happens before vowel sounds and shifts to dark-L if it is not before a vowel

- dark-L simply has more tension at the back of the tongue and is slightly longer or slower

Again, since dark-L is not crucial for excellent pronunciation, I rarely talk about dark-L with my students — our time is usually better spent on other aspects of pronunciation. However, if someone who has a very high level of pronunciation wants to tweak and perfect their English, then dark-L may be something they want to work on.

If I were coaching a non-native speaker who wanted to improve this detail of pronunciation, I would have a tendency to skip the term “dark-L” and just say that any time that an “L” does not precede a vowel sound, it sounds nicer and more similar to a native speaker if it has a little bit more tension in the back of the tongue and goes just a little bit slower.

P.S. Silent “L”!… Sometimes I have students who have not learned about words with silent “L”. So, in case you didn’t know, in all of these words, the “L” is silent (it has no sound): could, would, should, walk, talk, chalk, half, calf, folk, yolk.

Answers: Which words have dark-L? (in bold)

airflow / children / clear / example / explain / fall / follow / goal / light

longer / only / simple / spell / spell out / vowel / vowel sounds / while

You can find additional advice and practice for some common difficulties related to English “L” on my Patreon page! My Patreon has a supplementary article (with audio) on English “L” and includes practice on these areas:

- “L” vs. “R” (often a problem for Korean, Japanese and other Asian language speakers)

- “L” vs. “N” (often difficult for Chinese speakers)

- Correcting Ultra-Light-L (common for French and Spanish speakers)

- Avoiding Dark-L at the beginning of English words (an issue for some Russian speakers)

Patreon tiers range from $2 to $100 USD per month, and support my goal of creating a comprehensive online English pronunciation learning platform!!